|

From the Cassini-Huygens Website - Huygens Mission to Titan:

Back to

Astrobiology

This page is copied directly from the

Huygens website! It is to serve as a sort of mirror in case the Huygens

page becomes old and unlisted.

|

This artist's conception shows Titan's surface with Saturn appearing

dimly in the background through Titan's thick atmosphere of mostly

nitrogen and methane. The Cassini spacecraft flies overhead with its

high-gain antenna pointed at the Huygens probe as it nears the surface.

Titan's surface may hold lakes of liquid ethane and methane, sprinkled

over a thin veneer of frozen methane and ammonia. Most of the

brownish-orange color comes from more heavily processed hydrocarbons

present in Titan's atmosphere and on its surface. Artistic license has

been used to exaggerate the size of the orbiter, the sharpness of the

icy features, the tilt of Saturn's rings, and the visibility of the

planet through Titan's atmosphere. By Craig Attebery |

The European Space Agency's

Huygens probe ushered in 2005 with its landmark mission at Titan. After a

seven-year journey bolted to the side of the Cassini Orbiter, Huygens was set

free on Dec. 25, 2004. The Probe coasted for 21 days en route to Titan.

Probe Separation and Transit to Titan

Prior to the probe's separation from the orbiter, the triplicate "coast" timer,

or Mission Timer Unit (MTU) was loaded with the precise time necessary to turn

on the probe systems (about 4 hours before the initial encounter with Titan's

atmosphere). Then the probe separated flawlessly from the orbiter. Cassini

turned and imaged Huygens repeatedly as it set out on its 21-day coast to Titan,

with no systems active except for its wake-up timer.

Huygens separated from Cassini at 30 centimeters (about 12 inches) per second

and a spin rate of seven revolutions per minute to ensure stability during the

coast and entry phase. This rate was confirmed by the Magnetometer instrument on

the Cassini Orbiter. Five days following the release of the probe, Cassini

performed a deflection maneuver. This placed the orbiter on the proper

trajectory - missing Titan instead of impacting - to collect Huygens' data

during the probe mission.

Titan's nitrogen-rich atmosphere extends 10 times further into space than

Earth's atmosphere. This means the outer fringes of Titan's atmosphere reach

almost 600 kilometers (almost 400 miles) into space. When the probe detected

this region of Titan's atmosphere, the deceleration set off a sequence of events

leading to its perfect parachute descent.

Huygens was equipped with six science instruments designed to study the content

and dynamics of Titan's atmosphere and collect data and images on the surface.

All times are given in

Spacecraft Event Time (SCET),

Universal Coordinated Time (UTC)

|

Probe Release:

December 25, 2004 02:00 UTC

|

Probe entry at Titan:

January 14, 2005 11:04 UTC

|

Speed at Entry:

6 kilometers per second

|

Impact Speed:

5 meters per second |

Mission Duration:

2 hr, 27 min, 13 sec descent, plus

1 hr, 12 min, 9 sec surface |

Altitude of Cassini during the Huygens

Mission:

60,000 kilometers |

Data rate to Cassini Orbiter:

8 kilobits per second |

Total Battery Capacity of Probe =

1800 Watt-hours |

|

Descent

Through Titan's Atmosphere

Huygens made a parachute-assisted descent through Titan's atmosphere,

collecting data as the parachutes slowed the probe from super sonic

speeds. Five batteries onboard the probe were originally sized for a

Huygens mission duration of 153 minutes, corresponding to a maximum

descent time of 2.5 hours plus a half hour or more on Titan's surface.

In fact, they lasted much longer than that. These batteries were capable

of generating a total of 1800 Watt-hours of electrical power.

The probe's radio link was activated early in the descent phase, during

time the orbiter was flying overhead, "listening" for the probe. Not

long after the end of this four-hour communications window, Cassini's

high-gain antenna (HGA) turned away from Titan and pointed toward Earth.

| This artist's conception of the Cassini orbiter shows the

Huygens probe separating to enter Titan's atmosphere. After

separation, the probe drifts for about three weeks until

reaching its destination, Titan. Equipped with a variety of

scientific sensors, the Huygens probe will spend 2-2.5 hours

descending through Titan's dense, murky atmosphere of nitrogen

and carbon-based molecules, beaming its findings to the distant

Cassini orbiter overhead. The probe could continue to relay

information for up to 30 minutes after it lands on Titan's

frigid surface, after which the orbiter passes beneath the

horizon as seen from the probe. |

|

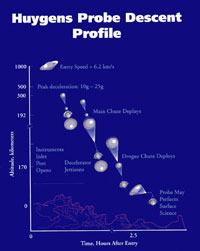

The peak heat-flux was

expected in the altitude range below 350 kilometers (217 miles) down to

220 kilometers (137 miles), where Huygens rapidly decelerated from about

21,600 kilometers (13,424 miles) per hour to 1,440 kilometers (895

miles) per hour in less than two minutes.

At this speed, the parachute deployment sequence initiated, starting

with a mortar pulling out a Pilot Parachute which, in turn, pulled away

the aft cover and deployed the Main Parachute. After inflation of the

8.3 meter (27.2 foot) diameter main parachute, the front shield was

released to fall from the Descent Module. Then, after a 30 second delay

built into the sequence to ensure that the shield was sufficiently far

away to avoid instrument contamination, the Gas Chromatograph Mass

Spectrometer (GCMS) and Aerosol Collector and Pyrolyser (ACP) inlet

ports opened and the Huygens Atmospheric Structure Instrument (HASI)

boom deployed. The Descent Imager/Spectral Radiometer (DISR) cover was

ejected two minutes later.

The main parachute was sized to pull the Descent Module safely out of

the front shield. It was jettisoned after 15 minutes to avoid a

protracted descent, and a smaller 3-meter (10-foot) diameter parachute

was deployed. The descent lasted about two and a half hours.

|

|

During its descent,

Huygens' camera returned more than 750 images, while the Probe's other

five instruments sampled Titan's atmosphere to help determine its

composition and structure. Huygens collected 2 hours, 27 minutes, 13

seconds of descent data, and 1 hour, 12 minutes, 9 seconds of surface

data, which turned out to be far more surface data than was ever

expected.

Every bit of data from Huygens was successfully relayed to the Cassini

Orbiter passing overhead, with the exception of a redundant stream

called "Chain A." Chain A's radio frequency was based on Huygens' Ultra

Stable Oscillator, designed for the Doppler Wind Experiment. While this

signal was not received aboard Cassini, it was received on Earth, thanks

to Radio Scientists using Earth-based radio telescopes at

Green

Bank and

Parkes. They were actually able to capture the tiny signal, now

being called "Chain C," directly from Titan! Telemetry data from Huygens

was stored onboard Cassini's Solid State recorders (SSR) for playback to

Earth. Huygens is managed by the European Space Agency. Complete details

on the mission objectives and science can be found on the

ESA Huygens Site.

|

Back to Top |